A Landscape with Ainu Kotans and the Repatriation of Ancestral Remains

Sapporo has been home to the Ainu since before Japan’s Meiji revolution. In the second year of the Meiji era (1869), the colonization program known as kaitaku (‘pioneering’) began. Under this policy, the Ainu lost not only their land, livelihood, language and culture, but even the remains of their ancestors. Today, many people think of the Ainu as living in the Shiraoi, Nibutani, Asahikawa and Akan areas, but Sapporo is also rich in Ainu history.

People live together with everything around them. In such a relationship there is no boundary or distinction between the animate and the inanimate. Could we not also say that the landscape is alive? Let us call such a notion the ‘living landscape,’ and head off on a journey around the living landscape of Sapporo.

About this field

The city of Sapporo, in Hokkaido, was built along the banks of the Toyohira River.

In 1869 the Meiji government renamed the island, ‘Ezochi,’ to, ‘Hokkaido,’ and established Sapporo as the regional capital. In 1871, the Colonial Development Ministry relocated its base here from the southern port of Hakodate. In the more than 150 years since, the city of Sapporo has developed into a prefectural capital with a population of almost 2 million. The academic institution that would later become Hokkaido University was founded in 1875 and boasts a vast campus site.

However, this view of history is seen from the perspective of the ‘Wajin’ (ethnic Japanese) population. From long before the Meiji era, and continuing to this day, Sapporo has also been a home to the Ainu people. But even today, the writing of history and the building of memorial sites in Sapporo city and Hokkaido University still excludes the point of view of the Ainu people.

In the Ainu language, ‘Sapporo’ comes from the words sat and poro, which refer to the ‘dry,’ ‘wide’ river which runs through the area. A river which the Wajin incomers renamed, ‘Toyohira.’ Despite their long history in the region, all trace of the Ainu villages and the people who lived around the Sapporo river before colonization have disappeared from the modern city. Here, we use documentary evidence to recreate some of the landscape with its Ainu kotans (villages), including the area around the Ishikari River, into which the Satporo flows.

There is a reason why we have chosen to use ‘landscape’ (Fu-kei) as a keyword, here.

People live embedded within a landscape. Rivers flow, mountains loom, the sun rises, the moon shines. As the seasons change, people live with the other people and creatures around them through pain, kindness and gratitude. In order to express this scene in which life is entwined, rather than the matter-of-fact ‘environment,’ the word, ‘landscape,’ much better reflects its living nature. People live together with everything around them. In such a relationship there is no boundary or distinction between the animate and the inanimate. Could we not also say that the landscape is alive? Let us call such a notion the ‘living landscape,’ and head off on a journey around the living landscape of Sapporo.

As well as being taken from Sapporo in the name of ‘research,’ a vast amount of Ainu ancestral remains have been brought to Hokkaido University from outside Sapporo, too. Most of them have not yet been returned. There are materials regarding this issue available on this website. These remains that were taken are of people who used to live here. For these people, Sapporo is also the hometown to which they should return. Returning the remains of these people to their home is one and the same with the revitalization of Sapporo’s living landscape.

This could be called ‘an alternative map of Sapporo,’ but it could just as easily be called ‘an alternative history of Sapporo.’ We hope that this part of the website can provide a portal to a decolonized Sapporo landscape, different from the one created through a biased colonial history (in Hokkaido, this is also called, ‘kaitaku history’).

We also sincerely hope that this website might be used to cure the Wajin who live in Sapporo from their collective amnesia concerning their home’s colonial past, to remind people that this is also the home of the Ainu people, and to reconnect them with the area’s Ainu history.

In addition, please be aware that some of the historical materials cited in this section of the website include images or language that is discriminatory towards the Ainu people. They have been included to give viewers an opportunity to see and experience some of the historical context of the issues discussed here. We believe that through confronting these things directly, they can be overcome. We ask for your understanding concerning these materials.

Respecting Ainu Place Names

Let’s try a little place name quiz.

Here are the names of places in modern-day Sapporo. Do you know their original Ainu names?

- Moiwayama

- Maruyama

- Kotoni

The answers are:

- Inkarushpe

- Moiwa

- Ha’samu

(NB. As there is no written Ainu language, transliterations into Japanese or English are not always phonetically accurate. Also, the Ainu area of Ha’samu did not cover the exact same area as the contemporary municipality of Kotoni.)

Ainu place names express the qualities of the areas they are describing. Inkarushpe means, ‘the place which one can always see.’ An appropriate name for the tallest mountain in the area, commanding an unparalleled view of the region. The smaller mountain next to it was called, Moiwa, which means, ‘small rocky mountain.’ The incoming Wajin shifted the name, ‘Moiwa,’ to Inkarushpe mountain, and renamed the smaller mountain, ‘Maruyama,’ after a similar mountain in Kyoto.

The original meaning of Kotoni is, ‘place of basins,’ which refers to the many small basins and hollows formed within and around Toyohira River’s alluvial fan, into which underground streams flow. This area covered from what is now the southern end of Hokkaido University’s Sapporo campus, down to the University Botanical Gardens, and across to the prefectural Governor’s Mansion. The name was moved westward by Wajin colonisers and used to refer to the area around the modern-day Kotoni train and subway stations. This area, through which the Kotoni-Hassamu River flows, was originally the site of the Ainu Ha’samu Kotan, and the name, ‘Hassamu,’ is now used to refer to the area to the northwest of contemporary Kotoni.

This one-sided renaming of places even affects the Ainu people’s ability to pray to the kamui (gods). Ainu Fuchi (a female elder), Kura Sunazawa, spoke about this problem. Kura’s husband, Tomotaro, was an excellent hunter. He respected the kamui, and never failed to observe kamuinomi (prayers to the Kamui) when he went into the mountains. When Kura and her husband went to a spring, named, ‘Kuromanbetsu,’ at the foot of Mount Taisestu, he suddenly became angry.

“What’s ‘Kuromanbetsu’? This is Komanpe’tsu! If I perform kamuinomi with the wrong name, the gods won’t hear my prayers” (Sunazawa 1990 Ku Sku’p Orushpe: The Stories of My Generation, Fukutake Publishing: 297).

“My husband always used to get angry about the way Wajin changed Ainu place names into words that didn’t have any meaning to them” (Sunazawa 1990: 298).

Offering prayers to the kamui is of fundamental importance to the Ainu. For example, Inkarushpe has also been worshipped as a sacred mountain which is home to kamui. Naming the place, ‘Mount Moiwa’ means that people’s prayers cannot reach the kamui. Names are that important. It’s not something that people just turn up and mess around with.

Place names are engraved with the history and wisdom of the people who created them. This is something that should be respected. Is there not some way we can return places to their old names? If that proves difficult, can we not use a dual name (like, ‘Inkarushpe-Moiwa’)?

Sapporo’s Four Ainu Kotans

There were Ainu kotans in and around what is now Sapporo city up until the early Meiji era (late 19th century). Alongside these kotans, the iwor (land and watershed set aside for fishing, hunting, collecting wild plants, harvesting trees, and so on) from which the residents sustained themselves stretched far and wide. So, where were these kotans?

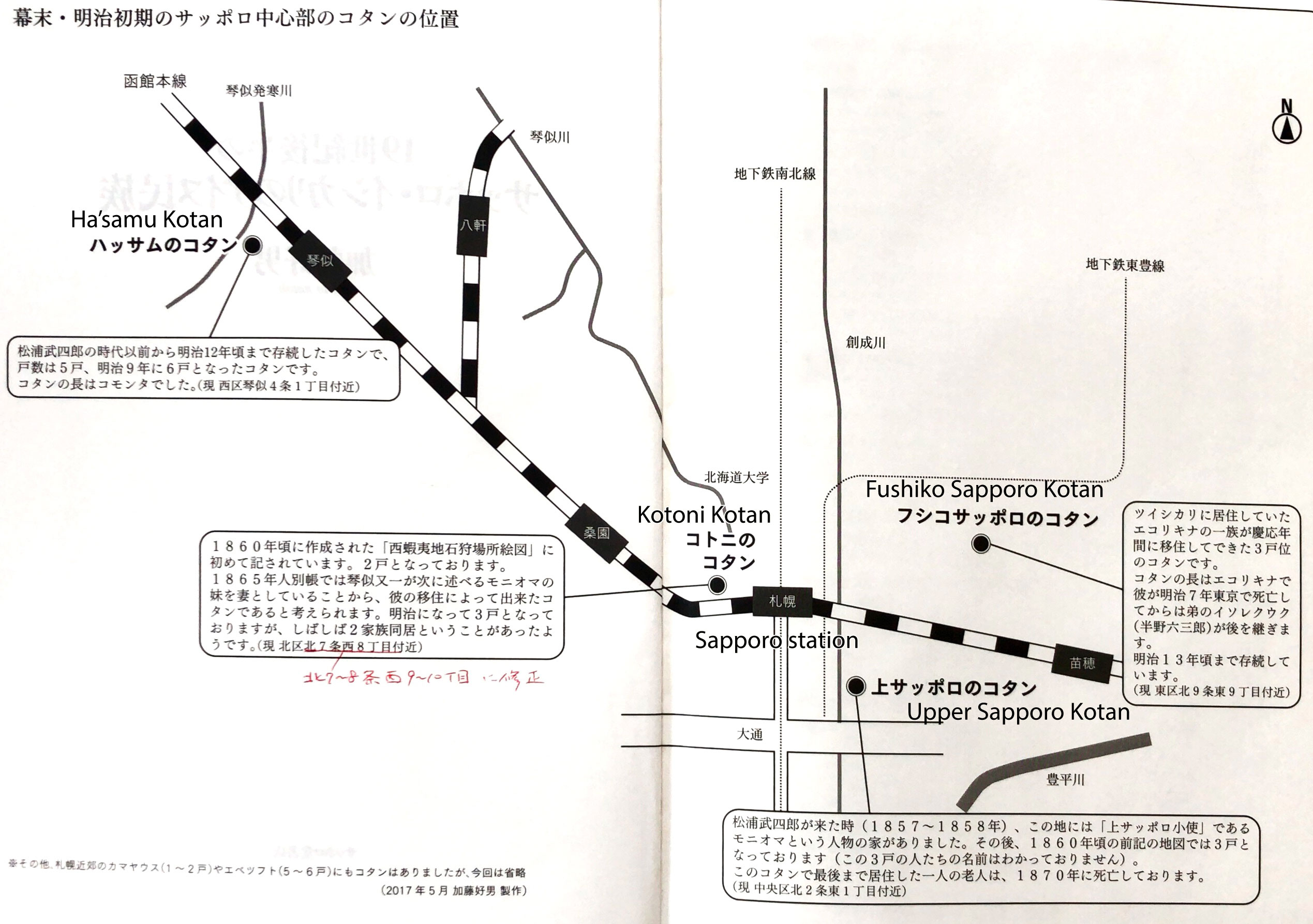

According to an investigation by Yoshio Kato, during the second half of the 19th century (from the Bakumatsu era to the early Meiji era), the center of modern-day Sapporo municipality was home to four Ainu kotans. The locations of these kotans are introduced on the map below.

However, please be aware that the website section entitled, B Journey to Kotoni Kotan, tells the story of the search for the location of this kotan. For those who wish to avoid any spoilers, we suggest that you read that section first, before coming back to this page.

Below are the names of the four kotans which Kato (2017, Ainu People at the End of 19 Century in the Ishikari-Sapporo Area, private edition) determined were located in the central Sapporo area during the late 19th century, introduced from west to east, along with the contemporary addresses which now occupy those locations. Please note that these locations are estimates based on comparison between 19th century documents and modern maps.

- Ha’samu Kotan (the area around Kotoni 4-jo 1-chome, West ward)

- Kotoni Kotan (the area around North 7-8-jo West 9-10-chome, North ward – this position was revised by Kato (2017b) but is considered by Shogo Miyasaka to have been located slightly further west, around North 8-jo West 11-chome. Link: B Journey to Kotoni Kotan)

- Upper Sapporo Kotan (the area around North 2-jo East 1-chome, Central ward

- Fushiko Sapporo Kotan (the area around North 9-jo East 9-chome, East ward)

When placed on a map, they look like this: